His soul-baring at the trial brings forth condemnation from the pulpit as well as from the new discipline of psychological observation, which analyses character in more scientific - but no more helpful - terms. In Thomson’s eyes, Roderick is surely guilty, not least because of his admission that he had no love for the dead man who both ruled the community and made Macrae’s life a particular hell. The most revealing evidence is provided by the prison surgeon, James Bruce Thomson, who holds ironclad views on the behaviour of the criminal class. But the truth of the events is pieced together via witness statements, postmortem reports, dodgy phrenologists and journalists setting down details of the trial. Macrae appears to have entered (with murderous intent) the house of his deeply unpleasant neighbour Lachlan Mackenzie, a local constable.

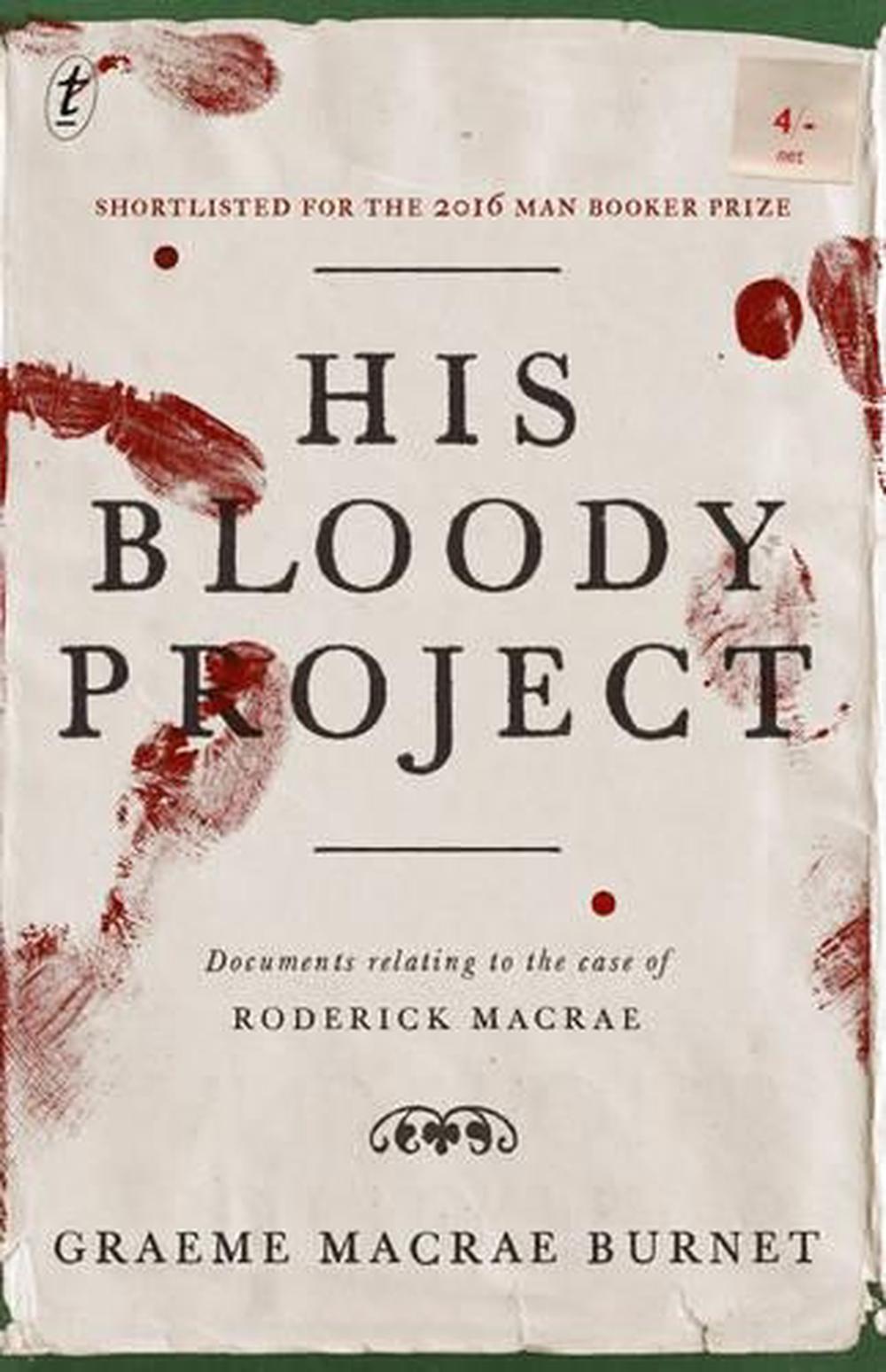

A young crofter, Roderick Macrae, wrote up the catastrophes of his life while awaiting trial in Inverness in 1869, accused of three savage killings. The wholly fictitious premise is that the author, Burnet himself, while looking into his own Scottish roots, discovered a fragment of a memoir that apparently set Edinburgh society of the time alight.

The subtitle of the book reads: “Documents relating to the case of Roderick Macrae”, and these ersatz papers build a picture of an insular Highland crofting community in the 19th century while also presenting a fascinating picture of attitudes to the criminology of the era. In this case, Burnet includes witness statements, postmortem documents on murder victims, a documentary account of a trial - and a lengthy memoir by the man accused of triple murder. His Bloody Project appears to channel a bookish version of the currently fashionable “found footage” film genre, in which verisimilitude is suggested by randomly cobbled-together documentary material forming a fragmentary narrative.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)